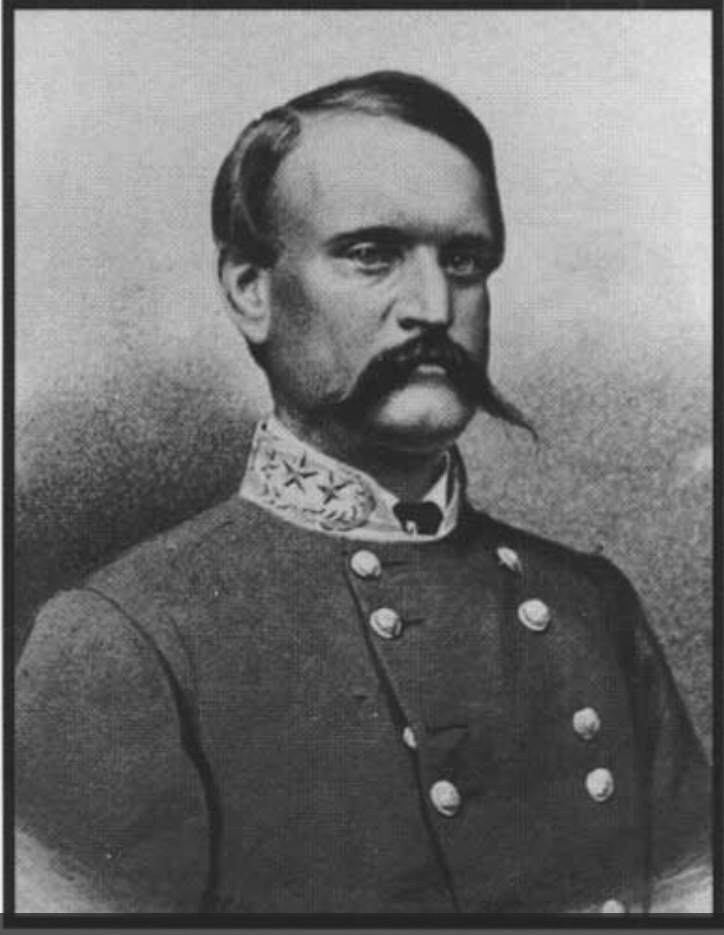

John C. Breckinridge represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress prior to becoming the youngest-ever vice president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861.

He was commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate Army on November 2, 1861 and, two weeks later, was given command of the First Kentucky Brigade, nicknamed the Orphan Brigade because its men felt abandoned by Kentucky’s Unionist state government.

Promoted to major general the following April, Breckinridge and his men performed well throughout the war, perhaps most notably at the Battle of Bull’s Gap in East Tennessee, wherein his troops won decisively on this day 156 years ago even as the outcome of the war became all but a foregone conclusion.

Promoted to Secretary of War in the waning months of the Confederacy’s existence, Breckinridge ensured the Confederate archives would be taken intact by Federal forces so a full account of the Southern war effort would be conserved for posterity.

Upon hearing of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, six days after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, eyewitness accounts recall a visibly upset Breckinridge to have said, “Gentlemen, the South has lost its best friend.”

Breckinridge lived as an expatriate after the war, landing in Cuba, England, Germany, Austria, Turkey, Greece, Syria, Egypt, and Italy, where he met with Pope Pius IX in Rome.

Refusing to seek a pardon, Breckinridge and his family settled for a time within eyesight of the American border in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada. He returned permanently in February 1869 after receiving word that President Andrew Johnson had granted amnesty to all former Confederates on Christmas Day.

Breckinridge declined all inquiries, including one made by President Ulysses S. Grant himself, about a return to politics, insisting “I no more feel the political excitements that marked the scenes of my former years than if I were an extinct volcano.”

Speaking as a private citizen in March 1870, he publicly denounced the actions of the Ku Klux Klan (as did Nathan Bedford Forrest). Breckinridge echoed his personal conviction regarding the social unrest of the time two years later when he supported passage of a statute that legalized black testimony against whites in court.

He died in 1875, aged 54, in his native Lexington, Kentucky respected fully — as Lee and Jackson before him — by compatriots and opponents alike.